Maryknoll sisters turn over educational programs to local leadership after three decades of compassionate service.

Maryknoll Sister Regina Pellicore summarizes the Maryknoll Sisters’ 33 years of service in Cambodia: “All along the journey, our mission has been to provide the care, love and support needed for a better life.”

Cambodia was still reeling from the deep trauma of the Killing Fields when the sisters arrived in 1991 following the Paris Peace Agreements. They were part of Maryknoll Cambodia, a team of Maryknoll priests, brothers, lay missioners and sisters sent to aid in the nation’s restoration.

“Cambodia was emerging from one of the most tragic episodes in the history of the world,” explains Maryknoll Sister Luise Ahrens, who was among the first four sisters assigned to the small nation in Southeast Asia.

From 1975 to 1979, the Khmer Rouge regime had caused the deaths of an estimated 2 million people — roughly a quarter of the population. Educated people, in particular, were targeted: doctors, lawyers, teachers, professors.

“Those who had soft hands or wore glasses or who spoke the French language were shot right there,” Sister Luise remembers being told by survivors. An entire generation of professionals, she continues, were “almost completely wiped out.”

The missioners soon found that Cambodia could benefit from various ministries.

Maryknoll Sister Luise Ahrens talks with students in the library of the Royal University of Phnom Penh, which Maryknoll sisters helped to develop. (Sean Sprague/Cambodia)

Sisters Patricia Ann Arathuzik, Dolores Congdon and Joyce Quinn, who were experienced in nursing, dedicated their efforts to health care. Later, Sisters Juana Encalada and Leonor “Len” Montiel — joined for a time by Sister Bernadette Duggan — worked in HIV/AIDS ministry: Cambodia had one of the highest rates of HIV in the world.

Because of her background in tertiary education, Sister Luise was approached by the minister of education to work at the Royal University of Phnom Penh, the country’s largest institution of higher education. “I asked him, ‘To do what?’” Sister Luise recalls. “He answered, ‘Anything you can.’”

Sister Luise’s colleagues described to her the university’s reopening just a decade earlier with two faculty members and 36 students: “There were no books left, no labs. The Khmer Rouge had kept pigs there to show what they thought of education.”

Over the ensuing 25 years, Maryknoll sisters helped to solidify programs at the Royal University. Sister Len, who has expertise in community organizing, taught in the emerging social work department. Sister Mary Little not only taught English, but also trained Cambodian staff to run the English language program.

Working with the university president, Sister Luise sought funding for staff salaries and opportunities for Cambodians to study abroad. She recruited and mentored international volunteers. The sisters also procured educational tools and developed the university library.

In other ministries, Sister Joyce had been working in partnership with three Cambodian nurses. In 1994 the sisters moved into Beoung Tum Pun, a huge, poverty-stricken area on the southernmost edge of the capital city. There Sister Joyce started the Community-Based Health and Education Program (CHEP) on the grounds of the Church of the Child Jesus. Sister Regina, a teacher, arrived a year later.

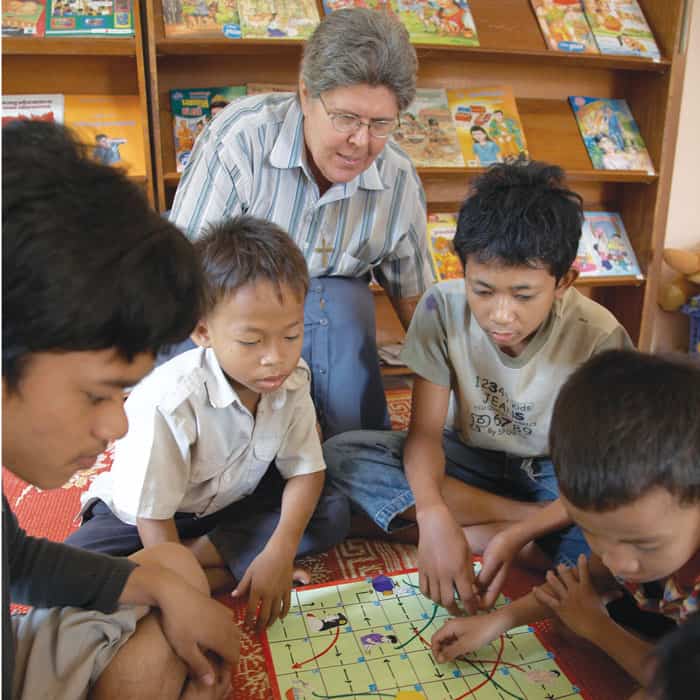

Maryknoll Sister Regina Pellicore engages with students in one of many educational projects run by the Maryknoll Sisters in Beoung Tum Pun, a marginalized area outside of Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh. (Sean Sprague/Cambodia)

It quickly became evident that along with medical services, training in basic hygiene and nutrition was needed. However, adults, who labored all day, were not as receptive as the children, who responded readily to songs and games.

The Child to Child program was the answer.

The international organization that runs this program reports that since the 1970s it has “partnered with and trained the world’s leading agencies to equip children with the skills to stay safe, stay healthy, and achieve their potential.” Its peer-based methodologies train child leaders who then transmit these skills to their families and other children.

Administrators and teachers at Beoung Tum Pun’s three primary schools had to be convinced to try the program; but once they saw its results, they welcomed it.

The program also encouraged teachers to integrate more participative learning in the classroom. “Our hope was that by modeling other ways to teach, they would adapt some of the more creative methods for their own subjects,” Sister Regina recalls.

The sisters’ project soon expanded. “Given our long-term presence in Beoung Tum Pun, the services of our programs continued to meet the needs of the community,” Sister Regina says.

Because many older children either never attended or dropped out of school, literacy classes were launched. The goal was to strengthen these students academically in order for them to integrate into a regular classroom.

Since English proficiency is required for many jobs and for higher education, Sister Ann Sherman spent a decade teaching English to middle schoolers.

The School Assistance Program was started to tutor students and to provide school supplies and fees through a scholarship program.

Maryknoll Sister Ann Sherman, who spent a decade in Cambodia, teaches an English class for middle school students in Beoung Tum Pun. (Courtesy of Ann Sherman/Cambodia)

“We support many students whose families live day to day,” Sister Regina says. She explains that the focus is reaching the poorest of Beoung Tum Pun’s 22,000 families.

Some are Vietnamese refugees.

To serve these families, Sister Mary — who also worked at the opposite end of the educational spectrum at the Royal University — founded two preschools. There, Vietnamese-speaking children learn Khmer, Cambodia’s official language; this eases their transition when they enter local government-run schools.

Working alongside non-governmental organizations and Cambodian entities, the sisters’ projects eventually reached each of Beoung Tum Pun’s five villages.

“We have been rebuilding the foundation of the country, especially in education, by keeping children in school, from the little ones through university students,” Sister Regina says. “Every child who learned to read, write and think critically about the future of Cambodia took a step in the right direction.” She adds, “We paved the way for those steps.”

A final example of how Maryknoll sisters brought education to their community-based projects is seen in the work of Sister Helene O’Sullivan. During her 20 years with survivors of trafficking, sexual abuse and domestic violence, the missioner incorporated vocational training in the shelters and programs where she served.

Maryknoll Sister Helene O’Sullivan instructs students at Horizons, a skills training program for low-income girls at risk for trafficking. (Courtesy of Maryknoll Sisters/Cambodia)

Most recently, Sister Helene founded Horizons, a vocational training project for girls. The students are helped to stay in school until ninth grade, when they can enter a two-year course that will qualify them for employment in top hotels with good salaries and decent working conditions.

The project transitioned to the auspices of Caritas Cambodia last year.

This year, the projects pioneered by Maryknoll sisters in Beoung Tum Pun will also be transferred to partner organizations and Caritas Cambodia. Several staff members are being retained to ensure continuity.

The Maryknoll Sisters will complete their mission in Cambodia in 2024. Their three decades of service were made possible through close collaboration with Cambodian teachers, nurses and university staff.

When asked what she sees as Maryknoll’s greatest contribution there, Sister Regina says, “Giving as many Cambodians as possible the opportunity to have a better quality of life.”

She adds, “We hope that each one we have worked with passes on this blessing to others.”

Featured image: Maryknoll Sister Mary Little cares for a child at one of two preschools the sisters founded for Vietnamese refugee children. The Maryknoll Sisters have carried out extensive educational projects in Cambodia for three decades. (Sean Sprague/Courtesy of Maryknoll Sisters/Cambodia)

![]()