Eighty years ago, when an executive order imprisoned Japanese Americans, Maryknoll missioners became their tireless advocates.

On Feb. 19, 1942, two months after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II, Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. That order forced 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent into unjust imprisonment. Maryknoll missioners responded with compassion, advocacy and service.

Since the 1920s, the missioners had been helping Catholic communities of Japanese descent to flourish on the West Coast, where many Japanese immigrants had settled. The Maryknollers nurtured their faith and the faith of their children in thriving parishes and schools.

But the bombing of Pearl Harbor immediately changed life for these communities. In an atmosphere of growing fear and mistrust, violence increased against anyone of Japanese descent, including those who were U.S. citizens and had never even been to Japan. Executive Order 9066 called for the establishment of military zones in a 60-mile radius on the West Coast and authorized the U.S. Army to evacuate from the area anyone deemed a threat to national security – especially those with Japanese roots.

At first, Maryknollers worked feverishly to protect as many Japanese Americans as possible. In Seattle, Father Leopold Tibesar spoke to members of Catholic organizations, urging tolerance. He made plans to move his parishioners out of the exclusion area, but an archbishop refused permission.

Maryknoll sisters at the Maryknoll Home for Japanese Children in Los Angeles tended 33 children in residential care. Worried these children would be imprisoned, the sisters were able to place 26 with extended family or in foster care outside of the exclusion zone. Sadly, the other seven were interned.

Sisters Bernadette Yoshimochi (l.) and Susanna Hayashi lived and served in Manzanar camp. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

A 1997 article in the Los Angeles Times reports how in 1942 Maryknoll Father Hugh Lavery, gravely concerned for the orphaned children, wrote to Colonel Karl Bendetsen, head of the Wartime Civil Control Administration, begging for leniency for the children. Bendetsen responded, “I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must all go to camp.”

Families of Japanese descent were forced into “assembly centers,” makeshift concentration camps in racetracks or fairgrounds. In Portland, Oregon, more than 3,800 evacuees lived in a livestock pavilion subdivided into compartments. At Santa Anita, a racetrack in Arcadia, California, hundreds of people lived in horse stalls. Later, the U.S. government built 10 longer-term camps, called relocation centers, for the exiles.

Maryknoll Father Bryce Nishimura, a Japanese American from Los Angeles, was 13 years old when he and his family were sent to Manzanar Relocation Center in Owens Valley, California. At 93 years old, he still remembers the barbed wire that surrounded the camp, and soldiers with pointed rifles stationed in guard towers keeping close watch on the 30 blocks of barracks that made up the camp. “We were eight children and my parents, all crowded into two rooms,” Father Nishimura says, adding that the internees ate in a mess hall and shared public bathrooms. He considers the term “relocation center” a euphemism for what really were concentration camps.

In these prison-like conditions, Maryknollers accompanied the people in whatever ways possible.

Father Lavery not only visited his parishioners in Manzanar, but also traveled to the other camps in Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, Arkansas and Idaho, checking on people’s welfare, baptizing babies and saying Mass. Later, journalist Harry Honda, a Japanese American who had been in the U.S. Army while his family was imprisoned in the camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, described Father Lavery as having a “10,000-mile parish.”

Father Tibesar moved from Seattle to Idaho when his parishioners were sent to the Minidoka internment camp there. Not allowed to live in the camp, he drove 36 miles each day to offer Mass, despite war rations on gasoline. Father Tibesar was able to acquire releases for college-aged prisoners to attend Quincy College in Illinois, where his brother was president.

At Minidoka, Maryknoll Sisters Marie Rosaire Greaney and Regina Johnson taught catechism and sacramental preparation and organized a choir. Sister Johnson later described this experience as the “gateway … into my life as a Maryknoll missioner.”

Father Hugh Lavery shakes hands with an internee in Manzanar relocation camp. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

Father Leo Steinbach included teaching catechism in his ministry at Manzanar, which resulted in numerous converts to Catholicism. Fathers John Swift in Amache camp in Colorado and Joseph Hunt in Tule Lake in California made time to address internees’ temporal as well as pastoral needs, shopping on Saturdays for families’ shoes and clothing. Their lists included thoughtful items such as lipstick requested by teenaged girls, or lemon drop candies for a grandmother to share with her grandchildren. As the young men in camp requested “Dixie Peach Hair Pomade,” that went on the shopping lists too. Father Hunt even collected pieces of string for the children to spin their tops.

The imprisoned children were allowed to leave the camps under supervision. Father Hunt organized excursions from Tule Lake Segregation Center to picnic areas among lava rocks. There the children could freely jump and splash in hot springs with no armed guard watching them.

Maryknoll Sisters Bernadette Yoshimochi and Susanna Hayashi were working in California when the war began. Born in Japan, both sisters were offered safety at Maryknoll headquarters in New York. However, they chose instead to accompany the people they were serving in Los Angeles.

On May 16, 1942, the sisters attended Mass at 5 a.m. with others bound for Manzanar camp. Father Swift, the presider, spoke of the new mission the sisters were undertaking. Once in Manzanar, they were prisoners, coping with the hardships other internees endured. As missioners, they taught catechism, organized children’s activities and kept the camp church in order. They also cared for many children classified as orphans.

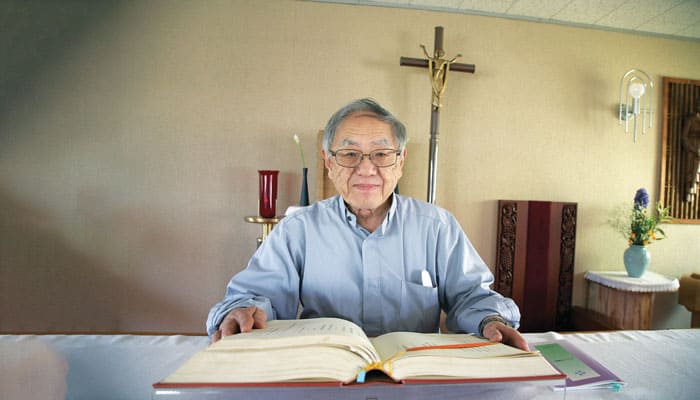

Maryknoll Father Bryce Nishimura, who was interned as a child in Manzanar Relocation Center, served in Japan for most of his priestly life. (Sean Sprague/Japan)

It was a grim time, but life always renews itself.

From the harshness of Manzanar, a future with Maryknoll emerged for Yae Ono, Thomas Takahashi and Bryce Nishimura.

Ono, a Japanese American citizen, had been baptized at 24 by Father Swift. She received her First Communion at St. Francis Xavier Church in Los Angeles in 1942. Soon after, her family was sent to Manzanar camp. There she and her sister taught catechism classes, assisting Father Steinbach and Sisters Hayashi and Yoshimochi.

During this time, Ono decided she wanted to join Maryknoll. With great difficulty, she was released from Manzanar and began her novitiate at Maryknoll in New York in 1944. She would be a Maryknoll sister for the next 68 years, until her death in 2012.

Father Takahashi was ordained a Maryknoll priest in 1953 and served as a missioner in Japan until his death in 1989.

Father Nishimura was ordained in 1956 and also served in Japan for most of his missionary life. Now retired, he lives in Los Altos, California. He attributes his priestly vocation to the influence of Father Steinbach in Manzanar camp. “He taught me that every human being is a person made in the image and likeness of God and deserves to be treated with respect,” says Father Nishimura.

Featured image: In this 1944 photo, Maryknoll Father Leo Steinbach talks to a group of young boys interned at Manzanar Relocation Center in California. (Maryknoll Mission Archives)

![]()