A journalist uncovers new information in the murders of four churchwomen, including two Maryknoll sisters, in El Salvador.

For those of us who went to Central America as young reporters in the late 1970s, as bloody civil wars were erupting in Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala, one of the biggest challenges was to find some fixed compass amid almost unfathomable levels of violence and cruelty. Regardless of our own religious beliefs, many of us found it in the Catholic Church, and nowhere more than among the Maryknoll Sisters. Over the years, they became a moral touchstone for me.

If you wanted accurate information that cut through the infamous “fog of war,” you went to the Maryknollers. No one had a deeper understanding of the human rights situation or responded more effectively to the needs of the poor. You were guaranteed lively conversation at a Maryknoll house, and even surprising moments of joy and laughter. Those visits felt like finding sanctuary — even though we knew that was an illusion once the Salvadoran death squads began to kill priests and church workers. No one was safe. Not even American religious sisters.

By 1980, death squads were operating with impunity, emboldened by the election of Ronald Reagan. Maryknoll Sisters Maura Clarke and Ita Ford were savagely murdered by five members of the Salvadoran National Guard 45 years ago, on Dec. 2 of that year, along with their friends, lay missionary Jean Donovan and Ursuline Sister Dorothy Kazel of the Cleveland diocesan mission.

Sisters Ita and Maura worked in the northern province of Chalatenango, aiding refugees from the first of the great rural massacres of the war, the slaughter of 600 people on the Sumpul River. Sister Maura had only recently arrived, replacing Sister Carla Piette, who drowned in a flash flood. In the town of Zaragoza, near the grubby Pacific port town of La Libertad, Sister Dorothy and Jean ran a shelter for women and orphans fleeing the violence in the north.

Three and a half years later, five guardsmen were convicted of aggravated homicide. To most of us who were there at the time, it was inconceivable that they could have acted without higher orders, and State Department officials such as Jeff Smith, the top lawyer assigned to the case, agreed. “It was always hard for me to believe that these guys acted on their own initiative,” he told me. But nothing could be proved.

Once you crossed paths with Maryknollers you never forgot them, and for the Maryknoll and Ursuline communities and a small group of lawyers, human rights advocates and surviving family members, the search for the truth was like an ache that never went away.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, as research director for the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights (now Human Rights First), I was privileged to work closely with Ita Ford’s late brother, Bill, a Wall Street attorney, and with lawyers from the Center for Justice and Accountability, on a series of lawsuits against two former Salvadoran defense ministers, José Guillermo García and Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova, who had been discovered living quietly in Florida as U.S. permanent residents.

They were eventually extradited to El Salvador, but while the churchwomen’s murders were part of the case against them, there was no evidence that they had ordered the killings — just that they had been derelict in exercising command oversight.

Since then, the same small group has reconvened periodically to keep the case alive. In 2022 I took one more attempt at uncovering the true story, and The New Republic magazine offered me an assignment to explore all the unanswered questions in depth: how the operation had been conducted, who commanded it, who gave the orders.

I found that as sources grew older, they spoke more freely, if only to unburden a troubled conscience.

Reexamining old evidence yielded new clues. The Freedom of Information Act unearthed documents long kept secret. Conscientious officials at the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (whose mandate has now been scaled back by the Trump administration) tracked down the most secret evidence of all, a clandestine tape recording of the National Guard sergeant who commanded the death squad. With this, and the aid of advanced digital technology, the last pieces of the puzzle fell into place. They formed a dark and chilling picture that traced the murders to the very heart of El Salvador’s death squads. The results were published in the May issue of The New Republic.

After this new two-year investigation, we know the name of the officer who commanded surveillance of the Maryknoll sisters’ arrival at El Salvador’s international airport the night they were killed. We confirmed that the sergeant in charge of the murder squad did indeed receive orders directly from a superior officer and alerted other security forces in the area to the imminent operation. We even discovered that the chief of police intelligence who directed the initial investigation of the crime was himself a death squad leader.

The surveillance operation at the airport was run by a Chile-backed National Police unit commanded by perhaps the most notorious of all Salvadoran officers, Lieutenant Colonel Domingo Monterrosa, whose Atlácatl Battalion later carried out the worst atrocity of the war, the slaughter of 1,000 unarmed civilians of the village of El Mozote. The retired American officer who trained the battalion confirmed to me that Monterrosa had been an asset of the Central Intelligence Agency.

The police officer who ordered the initial criminal investigation of the missioners’ murders, Lieutenant Colonel Arístides Alfonso Márquez — described in one secret CIA cable as “a very mean person who is to be feared” — headed what was probably the largest, best organized and most secretive death squad in El Salvador.

Another lieutenant colonel and especially notorious right-wing extremist, Roberto Staben, was responsible for gathering specific intelligence against Sister Dorothy and Jean in Zaragoza. The women were “terrorists,” he later told an American military attaché, according to one secret cable I unearthed. It had been “a routine wartime execution.” But what justified such a preposterous charge? the American asked. Because, Staben answered, they took “messages, medicines, shoes, clothes, and that sort of thing” to refugees.

Like all senior officers in the domestic security forces, these men came under the direct command authority of the vice minister of defense, Colonel Nicolás Carranza, the CIA’s principal asset in El Salvador, who was paid $90,000 a year for his services.

It was hard to go back to El Salvador for the first time in decades, to relive memories of that traumatic time. Yet it was also inspirational. I visited the quiet cemetery in Chalatenango where Sisters Ita, Maura and Carla are interred.

In a field near Santiago Nonualco, where the four churchwomen were murdered, a small memorial chapel receives a steady stream of pilgrims. Villagers have erected a small white monument decorated with sculpted angels, photographs of the women and text from the Beatitudes:

Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the land. … Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. (Matthew 5:5, 9)

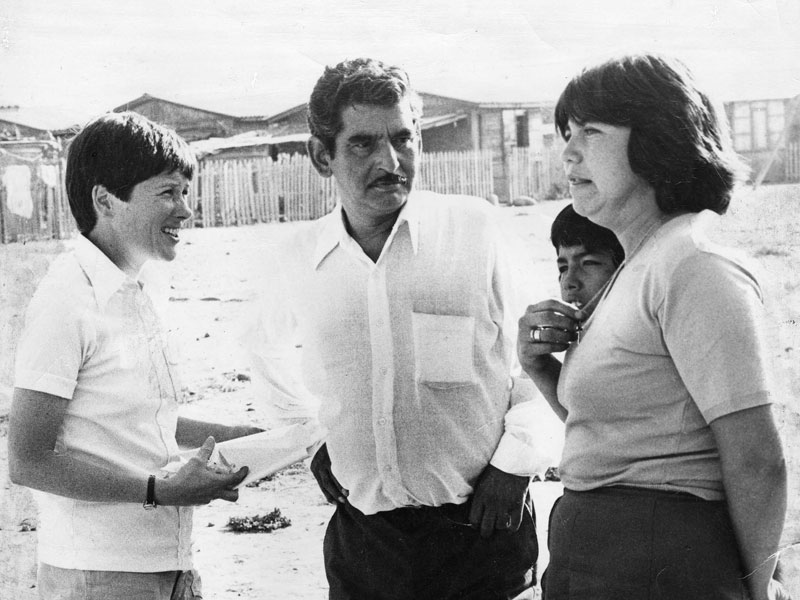

Featured image: During a memorial service in Santiago Nonualco, El Salvador, people hold pictures of four U.S. churchwomen killed there during the country’s civil war. (CNS/Jose Cabezas/Reuters/El Salvador)