A Maryknoll priest lives a life of happiness and purpose serving the poor like Jesus

Maryknoll Father Robert McCahill’s room holds few possessions. There’s one cup, one plate, two spoons, a knife, a vegetable peeler, one pot and a small kerosene stove. He owns three shirts and one pair of pants. There’s a baseball cap and a small bag with what he needs to celebrate Mass. A rough wooden shelf holds a missal and a tattered breviary, along with a notebook and scraps of paper with scribbled information about children who need help. His bicycle leans against a wall.

The missioner’s simple room is tucked away in the back of a small school in Srinagar, a village in the middle of Bangladesh. When the owner of the property met the Catholic priest and learned about his mission, he told Father McCahill he could live there, rent free. The school’s owner, like everyone else in the village, is Muslim.

A native of Goshen, Indiana, Father McCahill wakes up every morning at 2:30 and makes a cup of coffee. He then prays for an hour, usually sitting on his cot under a mosquito net. After 10 minutes of exercise, he says Mass, reads his breviary, then shaves. Finally, he makes breakfast, usually a boiled egg and a banana, before setting off on his bicycle for a day among the poor of Bangladesh.

It’s a routine he’s been repeating for almost five decades.

Following 11 years as a priest in the Philippines, Father McCahill arrived in Bangladesh in 1975 after the archbishop of Dhaka invited Maryknoll to the newly independent nation, still reeling from its war of independence from Pakistan. Upon completing a year of language studies, Father McCahill and four other priests asked the archbishop for permission to live and work among Muslims in the countryside, rather than do traditional parish work. Despite warnings from his advisors that Muslims might not accept priests and might even respond with violence, the archbishop agreed.

In the 47 years since, Father McCahill has lived in 14 different rural villages throughout the country. His goal is simply to be like Jesus.

Maryknoll Father Robert McCahill visits the family of Monna, a 12-year-old in need of support for health care services, in the village of Nopara near Srinagar. (Paul Jeffrey/Bangladesh)

“I’m a Christian so I want to help people. That’s what Jesus did,” says Father McCahill, who is known to many Bengalis as Bob Bhai — Brother Bob. “Jesus went around doing good and healing. So I go around on my bicycle and do some good. What Jesus did, I try to do.”

Since early in his ministry, Father McCahill has focused on helping children living with disabilities or other health challenges. That may be as simple as obtaining medicine or an appropriate wheelchair, but more often involves connecting them to health care providers for everything from physical therapy to surgery. The missioner will make appointments at clinics and then accompany the child and parents to assure that all goes well.

Helping is seldom easy, however.

“The poor are afraid,” Father McCahill explains. “Sometimes hospitals have a reputation in Bangladesh as a place you go to get ripped off or to die.”

Nazmul Khan Suzon, a journalist in Srinagar who befriended Father McCahill and introduced him to health care workers in the region, says the missioner is famous throughout Bangladesh. “All the doctors know him. That he’s a Christian priest doesn’t bother people,” Suzon says. “People are afraid that if they go to the hospital, it will cost them a lot of money. Bob Bhai gives them better options, a better life.”

Yet Father McCahill stays only three years in each place.

“Every time I go into a new town, there’s a year of suspicion. People suspect I’m there to convert them. But I keep at it, and by the second year, some trust has developed,” he says. “People stop me on the street or approach me in the tea stalls to tell me about a child who needs help. By the third year, they’ve begun to develop some affection for me. At the end of that year it’s time to move on and start anew.”

Maryknoll Father Robert McCahill visits 8-year-old Jair and his grandmother, Rohima, in the village of Batabhog near Srinagar. (Paul Jeffrey/Bangladesh)

As a Catholic priest living in villages where almost everyone is Muslim, except for a small number of Hindus, Father McCahill is frequently asked why he’s there. That conversation often takes place in tea stalls where he stops during the day to drink hot tea or eat a simple meal. At times a crowd gathers to listen — or at least to stare.

“When people ask me why I’m here, I always bring Jesus into it. He’s a prophet for Muslims, they appreciate him, so when I start talking about Jesus, whom they call Isa, no one suspects me of conversion,” he says. “Some people think the touchstone between Christians and Muslims is Mary, because she’s often mentioned in the Quran. But I think the touchstone is Jesus. We share Jesus. They don’t think he’s God, obviously, but they certainly understand when I tell them that Jesus is my model in life.”

Father McCahill says he has never experienced the violent rejection that worried the archbishop’s advisors. He admits that one time someone did knock off his hat. And once in the market a man hit him with a cane. “But he was a nut. And the other people there did not approve of what he did,” he says.

Instead of rejection, Father McCahill says he has received amazing hospitality — especially when people learn how he helps children in their villages.

“The people around me are learning that Christians are their friends, that we love them and want to be with them and do things together,” he says. “When they see what I’m doing, they are favorably impressed, and that changes their mentality towards Christians.”

Father McCahill is clear about what he is doing.

“This isn’t interfaith dialogue. It’s mission,” he says. “It’s what we should be doing, living among people of other faiths and doing something with them.”

To reach villages in rural Bangladesh, Maryknoll Father Robert McCahill travels mostly by bicycle, even in the rain. (Paul Jeffrey/Bangladesh)

Just as Father McCahill represents the Christian faith to Muslims who don’t personally know other Christians, so he helps Christians in the United States understand far-away Muslims.

Ever since arriving in Bangladesh, Father McCahill has written regularly to family and friends back home before Christmas, relating his adventures in mission. In 1984, he sent his letter to the National Catholic Reporter (NCR), and since then the newspaper has published his Christmas letter every year.

“One of the reasons for my yearly letter is to give examples of normal people living their lives,” says Father McCahill, who still patiently bangs out the letter on a manual typewriter that friends keep for him in the capital. “The Catholic bishops of Asia have stated that rather than focusing on conversion of people of other faiths, we should strive to live in harmony with them.”

Tom Fox, who was NCR’s publisher when it started carrying the priest’s annual letter, calls Father McCahill’s missives the most interesting missionary letters to pass through the paper’s newsroom.

“They’d come on old airmail stationery and were shocking in their unique witness to the faith,” Fox says. “Each letter was personal and would tell simple, understandable stories about his life and encounters among his friends. Father Bob’s love and life and witness was always gloriously displayed in simplicity. He seemed to live in rich poverty.”

Tom Roberts, NCR’s editor for several years, compares Father McCahill’s letters to those of communities in the early Church.

Maryknoll Father Robert McCahill visits Sabbir, a 14-year-old with disabilities in the village of Atigao. The priest has spent nearly 50 years helping children with medical challenges. (Paul Jeffrey/Bangladesh)

“His missives told of a solitary soul, a wanderer through cultures so very far from the conceits of first-world Catholicism. This simple man proclaiming the Word without words,” Roberts says. “It was, I often thought, the most authentically Christian thing we printed all year.”

When he’s done making his rounds each day, Father McCahill pedals home and fires up his kerosene stove. He cooks rice and lentils along with potatoes or string beans or okra. He stirs in a packet of spices that cost him five takas, about five cents.

“I cook that in one pot for 12 minutes. It’s the same meal every day, and I never tire of it,” he says.

Father McCahill, now 86, can’t see himself retiring from his mission.

“Last time I went back to the States they sent me to a doctor, and I spent almost a month doing excessive tests. Finally, they said I was in terrific health and could leave,” he says.

“And if I die here, so what? The purpose of life isn’t longevity. The purpose of life is love. I have found a way to love, and I constantly thank God for the astonishing invitation to a life of happiness and purpose.”

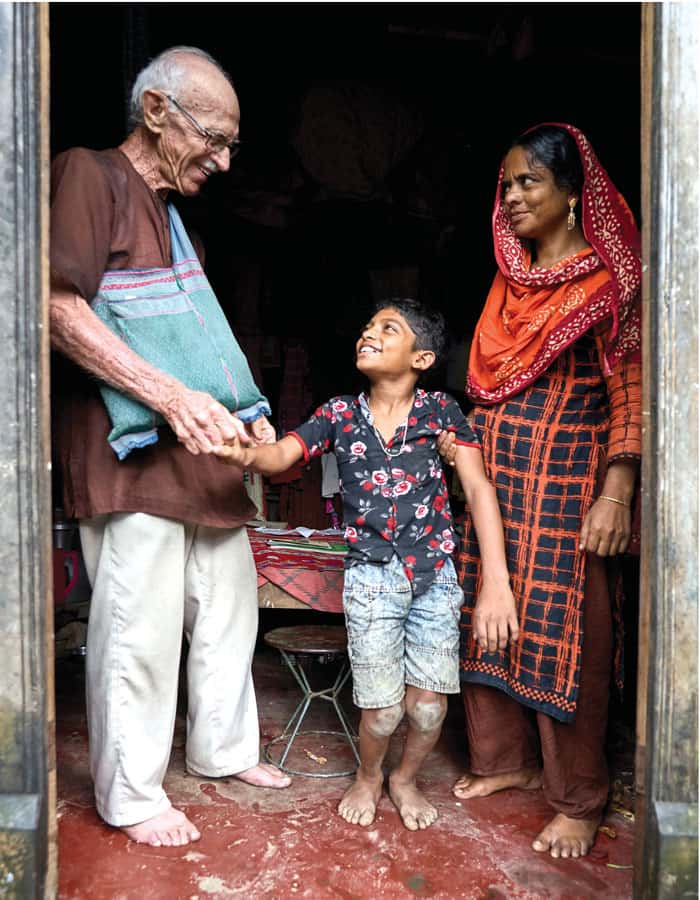

Featured image: Maryknoll Father Robert McCahill visits Jamila, a 9-year-old girl with disabilities, and her family in Baligao, a village near Srinagar, Bangladesh. (Paul Jeffrey/Bangladesh)

![]()