Returned Maryknoll Lay Missioner Susan Nagele remembers Bishop Paride Taban of Torit, South Sudan, as a wise and compassionate leader with a vision for peace in a war-torn country.

By

“I want you to examine a prisoner of war,” he told me in the dead of night. I was traveling with our Bishop Paride Ibrahim Taban, whom we all called “Taban.”

Our journey inched over a rutted path that connected the southeastern Sudanese Diocese of Torit to northern Kenya. The Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), a guerrilla movement in the Second Sudanese Civil War, was running a prisoner of war camp in the bush near the border. We arrived at 11 p.m. I kept my head down and followed the torch of my good shepherd past vague tall, slender and poorly clad rebel soldiers.

We stopped before an elderly, wizened soldier sitting on a thin piece of plastic with legs straight out in front of him. His name was Jamuus, which means “buffalo” in Arabic. Other than a thin blanket, he was naked. At that moment, we were all enjoying a cool breeze that swept away the ferocious daytime heat. The air would soon turn bitter cold without clouds above to trap the warmth emanating from soil and stones.

The two men both grew up in this diocese, but with different mother tongues. Jamuus was educated in Arabic and fought for the North. Therefore, the bishop spoke to him in Arabic. They were good friends. My patient was well known for his bravery and skill as an officer in the army of the Sudanese government. The SPLA had captured a valuable prize and reduced him to nothingness. He allowed me to examine him with my penlight and stethoscope as I knelt at his side on the flimsy tarp, painful stones digging into my kneecaps.

Taban asked about food, and he stretched out his hand to retrieve a small tin can from the corner of his plastic sheet, half filled with dry, caked sorghum. My stomach wretched and I swallowed hard to control it. A human body that consumed such “food” would surely be harmed, but it was all he had.

It was obvious that my exam would be his best treatment. He needed to know that the gentility of my hand was meant to convey kindness and concern. I gave him some vitamins and medicine to remove worms. The bishop gave him a new, thick blanket. Neither of us expected him to own any of these gifts for very long. His guards would help themselves immediately after our departure. But the bishop had been a prisoner of war himself for one hundred days in an SPLA camp. He knew what this visit would mean to his friend — everything.

I had first met this bishop in Nairobi, Kenya, at the Association for Member Episcopal Conferences in Eastern Africa. Apparently once, when he had arrived at the gate of this formidable modern compound, the guard had angrily rebuked him for trying to enter at nighttime, shouting that they didn’t admit any refugees. Taban sported a full and sometimes scruffy beard. He often traveled in clothes suitable for a journey that might be challenged by mud, rocks and the bush in general. He could easily resemble, as well as smell like, the sheep of his flock.

He had requested missionary priests, sisters and brothers to help serve the people of his diocese in the southern Sudanese state of Eastern Equatoria. It was de rigueur for a Catholic bishop to omit lay people in his request. I was being informally interviewed over lunch, and he was a very busy man. I wouldn’t get another chance to talk to him.

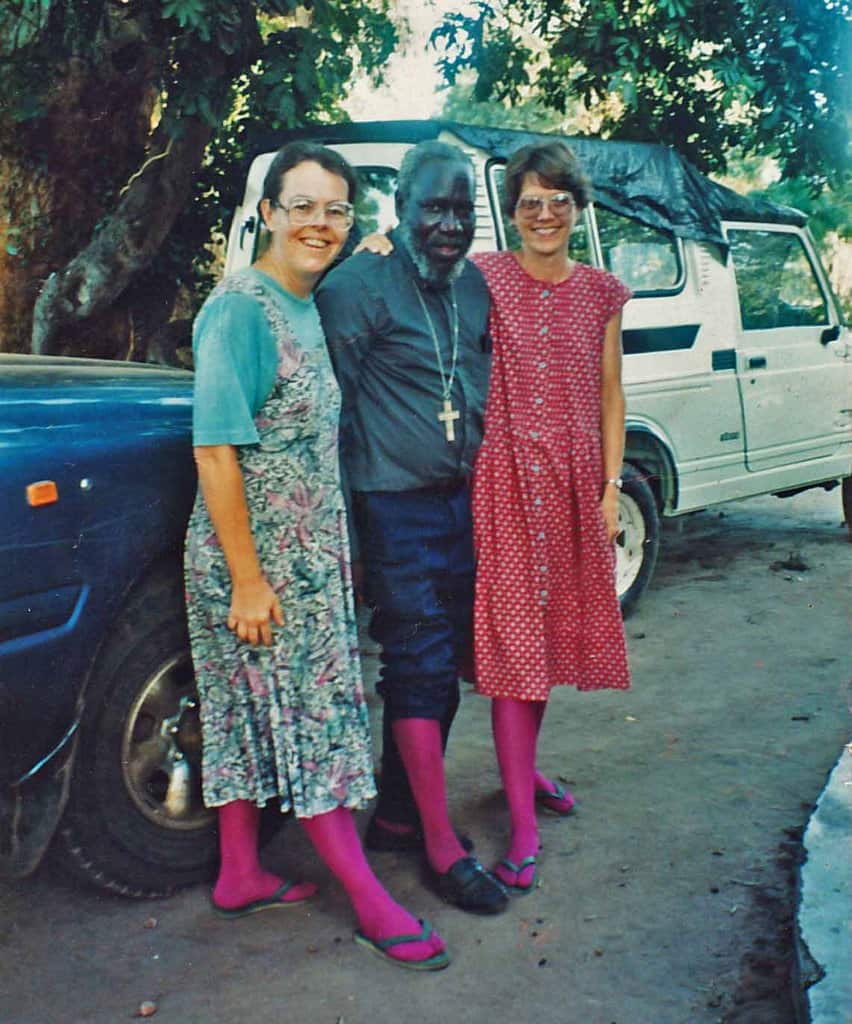

Bishop Taban with Maryknoll lay missioners Susan Nagele (right) and Liz Mach (left) in 1992. The author says Archbishop Taban had a good sense of humor. One day he was wearing red stocking and the two women chided him for the regal attire, saying that they would like the same. Some time later he arrived with a similar pair of socks for each of them.

I asked him if he would take a lay person. His diocese had been decimated by constant war. The needs were huge, and I looked respectable enough. He looked me up and down and said, rather curtly, “Yes.” His love for his sheep was not constrained by the routine of the past. I wasn’t sure what he thought of me. Time would tell.

I worked in his diocese for 12 years in health care. Sometimes we traveled together. On another trip, both of us were part of a convoy of diocesan personnel that included several priests and another female lay missioner, once again heading to northern Kenya in the dead of night. It was cooler to travel after sunset, and local bandits couldn’t see what was coming in the dark. While the would-be robbers slept, we crawled along over an international road that was never worthy of the image that title conjured up in my mind.

This particular journey landed us in Lokichokio, Kenya, at 2 a.m. Taban went to a local business man to find a place to sleep. Only one room with two beds was available. The bishop ordered the two of us women to take the room. He and the five Irish missionary priests in tow would stretch out on wooden benches encircling the cement slab outside our room. We women gratefully followed his orders. It would be only one of many instances where this shepherd made sure every one of his sheep was safe.

Taban travelled often, advocating for southern Sudan in other parts of the world. The times when he was present in the diocese were rare opportunities for me to listen to his stories and learn from him.

When he was a parish priest in a rural village among his own ethnic group, a man was brought to him who had been gored by a bull. The unfortunate herder lay on a locally constructed bed carried by his neighbors. Taban was the most trusted and well-educated person in a place where trained medical personnel didn’t exist.

The man lay supine with his abdomen split open. His intestines glimmered in the rays of sunlight that Taban used to assess the predicament. Calmly, he drew on common sense and got busy. Using clean water from a borehole, he gently washed away the dirt and grass that clung to every crevice and corner of the exposed insides. When that laborious task was finished, he gently put the man’s bowels back in his abdomen. Next, he threaded a sewing needle with white cotton thread and gently approximated the skin edges. They came together by pulling the stitches and tying them carefully but not too tightly. If there was bleeding, he dabbed and pressed the spot until the bleeding stopped.

When everything looked dry, he put a clean cloth over the wound and wrote a letter explaining what he had done. With paper in hand, the villagers carried the man north to the capital city of Juba in search of qualified medical specialists in the government hospital. The man was admitted and observed carefully. Without any sign of infection or intestinal blockage, he healed quickly and was sent home. There was no need for anything further to be done.

I was dumbfounded. I am a physician, but if that man had been brought to me, my mind would have registered every possible complication in light of the lack of medical equipment I assumed was essential. I would have been overwhelmed with fear. Taban taught me to keep my head on straight and do my best. Paralysis would only ascertain death.

Most Sudanese who survive to their fifth birthday are fit. Taban was one of the fittest. He never drank alcohol and chose a vegetarian diet, avoiding animal products when possible. He didn’t want people killing their only goat or chicken for him. He also claimed he never knew if the animal had been raided, and he didn’t want to be eating stolen meat.

A story I heard repeated on more than one occasion described a journey made in a convoy from the capital, Juba, to Torit, the seat of his diocese. The government was still in control of Torit and the SPLA was besieging the town. People were dying of starvation.

Taban had organized 70 trucks filled with food to make the 84-mile trip, escorted by the government army. The government commander strategically placed Taban’s vehicle at a certain place to protect others fore and aft.

SPLA rebels viewing the crawling parade from a range of hills in the distance knew exactly where the bishop was seated. They had been ordered to take him out. His mission of mercy to feed the starving was considered an act of treason against the “gallant, liberating” forces of the SPLA. But the soldier with his finger on the trigger couldn’t pull it.

Thirty-one days after leaving Juba, the food reached Torit. There were 20 fewer trucks and many wounded travelers, but Taban was not among them.

Taban was well known internationally and received many honors and awards for his peace-building work, including from U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and the archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby. In 2010 he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Voice of the Voiceless.

Hopefully these awards have inspired others around the world by the way this shepherd has lived his life. But such awards don’t mean much to those of us who lived with him, ate with him, prayed with him and were loved by him.

Over the course of 30 years in East Africa, I worked with five African bishops, one Irish bishop and countless clergy. Many were good shepherds of their flocks. A few were extraordinary. Taban was one of those who made every person feel like a member of the family, a person whom he would protect and love as his own. In the end, that is the measure of his achievements and, for us, his holiness.

Featured image: Bishop Paride Ibrahim Taban, who served as Bishop of Torit, South Sudan, from 1983 to 2004, is shown in an undated photo. The founder of Kuron Peace Village, Bishop Taban died on Nov. 1, 2023 and posthumously received an Opus Prize for his lifelong dedication to the residential peace project. (Courtesy of Maryknoll Lay Missioners)