Maryknoll Sisters in Tanzania provide education, hope and empowerment for pastoralist girls at the Emusoi Centre.

Maryknoll Sister Mary Vertucci recalls her first assignment to Tanzania five decades ago. “When I came here, I had a deep sense I was following this call to somehow minister to people in need,” she says. “I found myself teaching girls.”

Sister Vertucci, 77, runs the Emusoi Centre, a school for pastoralist girls, which she founded in 1999. “Emusoi” means “a place of discovery and awareness” in the language of the Maasai, one of the pastoralist peoples who live off of herding livestock on the savannas of East Africa.

“When the girls come, sometimes they’re so shy they don’t talk, they don’t look at you,” says Sister Vertucci. “A change happens even within the first few months as they gain self-confidence. It’s a wonderful transition to see.”

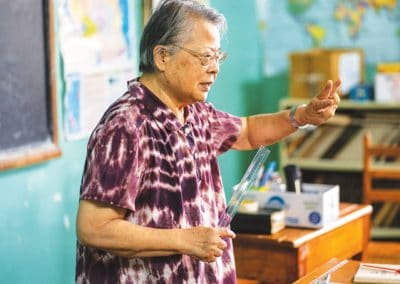

Maryknoll Sister Lekheng Chen teaches a class in Arusha; a student participates in a lesson. (Gregg Brekke/Tanzania)

The center’s compound and adjoining home for the sisters are nestled into the side streets of Arusha, Tanzania, a bustling commercial hub in the highlands of the country’s north central region. The town serves as the gateway to Mount Kilimanjaro and safari tourism, surrounded by farm and grazing lands.

Although the tribespeople in the region interact with the modern world as they bring their cattle and milk to market — or purchase cell phone minutes — their societies remain bound by centuries-old traditions and cultural norms.

Before she founded Emusoi, Sister Vertucci, who is originally from New Brunswick, New Jersey, studied gender roles and familial expectations as a research assistant for the Pastoral Research and Development Program in Tanzania. She found large disparities in educational admissions and outcomes between boys and girls in pastoralist communities, even though the government provides equal education in village schools.

Emusoi graduate Teika Simango, who went on to college and law school, works as the center’s legal advisor and program officer. (Gregg Brekke/Tanzania)

“The number of girls in primary school is much less than the boys, probably about two-thirds boys to one-third girls,” she says. Girls are often kept home to help with housekeeping, farming or tending the family’s animals. “Where there are two sisters, they may alternate the weeks they attend classes.”

Sister Vertucci explains that this inconsistency and lack of social encouragement decreases the number of girls able to pass the exams that would allow them to attend secondary schools. Furthermore, many girls are married off at puberty — further reducing the number of pastoralist girls who advance past an elementary-level education.

The center offers bridge classes to help girls make the move from primary to secondary school in a one-year residential setting. While foundational subjects such as English, writing, civics, math and science are taught, Emusoi also provides a pathway for girls to learn about life outside their villages. They interact with women and other girls in a safe and fun environment, and grow in creativity and independence.

Emusoi’s staff includes former students and two other Maryknoll sisters, Sisters Jareen Aquino and Lekheng Chen. They oversee two classes of up to 30 students per term. Graduates of the program are accepted into residential secondary schools around Tanzania. The success rate is very high — 85% of Emusoi-educated girls make the transition to secondary school, compared to less than 10% (in some areas, as low as 4%) in Tanzania.

For many girls, the Emusoi Centre is a refuge.

Emusoi student Neema (far left) visits her family in her home village during a program break. After graduating from the center, Neema went on to earn a diploma in environmental health. To date, some 2,000 girls have graduated from Emusoi. (Courtesy of Mary Vertucci/Tanzania)

“One of the girls came from ‘the back of the beyond’ — a very remote area,” Sister Vertucci recalls. “When she went home for break, her father wanted to marry her off without her consent. … So she lived here until she finished school and went to university.”

For some families, a daughter leaving the village can present an economic hardship. They may have received payment against a dowry for many years leading up to the marriage. “In the beginning, when we first started, sometimes the fathers would come to us and say, ‘If you take my girl, then you have to pay back the cows we’ve been receiving for her dowry,’” Sister Vertucci says.

Yet through persistence and visible results, the Emusoi Centre is changing the perception of girls’ education as a loss to their families. The testimonies — and the confidence — of the 2,000 graduates of the program are the key to bringing change, even if slowly.

Former student Teika Simango, a college and law school graduate, works at the center as its program officer and advisor. She says that many parents now ask to send their daughters to Emusoi.

“When you go [to the village] for the holidays, a lot of people will say, ‘My daughter finished standard seven, please take her with you,’” Simango says. “They’ve changed. It’s like they’ve broken the ice. Now they know that education is good for girls.”

During a field day, students engage in games in order to gain confidence and to build community across tribal divisions. (Gregg Brekke/Tanzania)

Recent graduates Flora Leiyo and Dianes Saikong return to visit during their breaks from teachers’ college. Leiyo says she tells parents that “every child who has been born has a right to get an education, has a right to study.”

Saikong says she is motivated by Emusoi to mentor younger girls. “I want to use what I’ve learned here to inspire, to educate my fellow girls,” she says.

An important part of learning at Emusoi is social development. For many of the girls, the isolated nature of villages and tribal areas means that meeting someone from another part of Tanzania is akin to meeting someone from another country. Games, team-building exercises, music and chores bring the girls together in shared activities to form bonds.

“When the girls come here, they are sometimes overwhelmed,” says Sister Aquino, 45, who has taught at Emusoi since 2011. “And then, after hanging out together, being with them in the classroom, challenging them, playing and laughing with them — they come up to you and confidently say, ‘Hi Sister! How are you?’ It’s so good to see how they blossom in confidence.”

Emusoi graduates Dianes Saikong (left) and Flora Leiyo return to the center in Arusha to mentor younger girls during breaks from teachers’ college. (Gregg Brekke/Tanzania)

The joy and confidence of the students at the Emusoi Centre is infectious — from thoughtful questions for visitors, to laughter between members, to shared responsibilities around the school. It’s easy to see that lives are being changed.

Even more, current and former students alike express gratitude. They say they are thankful for the opportunity to advance in their education and equally grateful for the life lessons of empowerment and self-worth.

Through the center’s student government and an enrichment course, the life skills class, Sister Vertucci says the girls “are encouraged to speak out, to think for themselves and to govern themselves.”

She has seen the program’s results in its many graduates. “They keep saying to me, ‘If you weren’t here, where would we be? We would be grandmothers already with no chance of education, but now we’re able to be independent and to be equal partners with our husbands.’”

Sister Vertucci summarizes her decades of ministry to pastoralist girls in simple terms. “Being with them, accompanying them, supporting them and encouraging them in their own journeys … As the Bible says, toward ‘life to the full’ [John 10:10] — that has been my motto.”

Featured image: Maryknoll Sister Mary Vertucci (gray hair), who founded the Emusoi Centre for pastoralist girls, visits her students’ homes in remote villages. (Courtesy of Mary Vertucci/Tanzania)

![]()