Maryknoll Father John Waldrep oversees a program in Tanzania to stop discrimination against people with albinism.

Aas the bright winter sun bakes the dusty red clay on the grounds of St. Theresa of the Child Jesus parish compound in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, small groups of people wander in to find refuge under a large shade tree. Soon, some 20 people have gathered to share their experience with the ministry initiated by Maryknoll Father John Waldrep for people affected by albinism.

People with albinism — which is characterized by light or pink skin — have a genetic trait that causes them to produce little or no melanin. Health issues are common, including cataracts and other vision problems and a high incidence of skin cancers, since their skin gives little protection from the sun’s rays. It is estimated that more than 90 percent of people with albinism in Africa will die before they reach the age of 40, most of them from skin cancer.

Father Waldrep, who was assigned to Tanzania in 1990, says that people with albinism experience many forms of social and economic discrimination. Historically, infanticide against children with albinism was practiced in rural areas. Where tribal practices prevail, there are still accounts of people with albinism being hunted down and skinned or dismembered — their skin or body parts worn (and even sold) as magic talismans.

Between 2000 and 2019, 76 people with albinism were killed in Tanzania and 182 people survived other physical attacks, according to the non-profit organization Under the Same Sun, which works to end discrimination and violence against persons with albinism. (Rather than using the term “albino,” the organization prefers “people with albinism” to “put the person ahead of their condition.”)

“If you ask, many people kind of see albinism as a curse, and a lot of people with the condition see themselves as cursed,” says Father Waldrep. “I hoped there was a way we could help them understand they’re really not cursed.”

Seven years ago, the missioner saw an opportunity to act.

“In the beginning there were a couple of people who sought me out,” says Father Waldrep. The missioner explains he provided help for their struggling families.

Word spread about the priest who was accepting of people with albinism, and more people with the condition stepped forward. In the hopes of increasing understanding of albinism, Father Waldrep proposed a seminar, and the community responded positively.

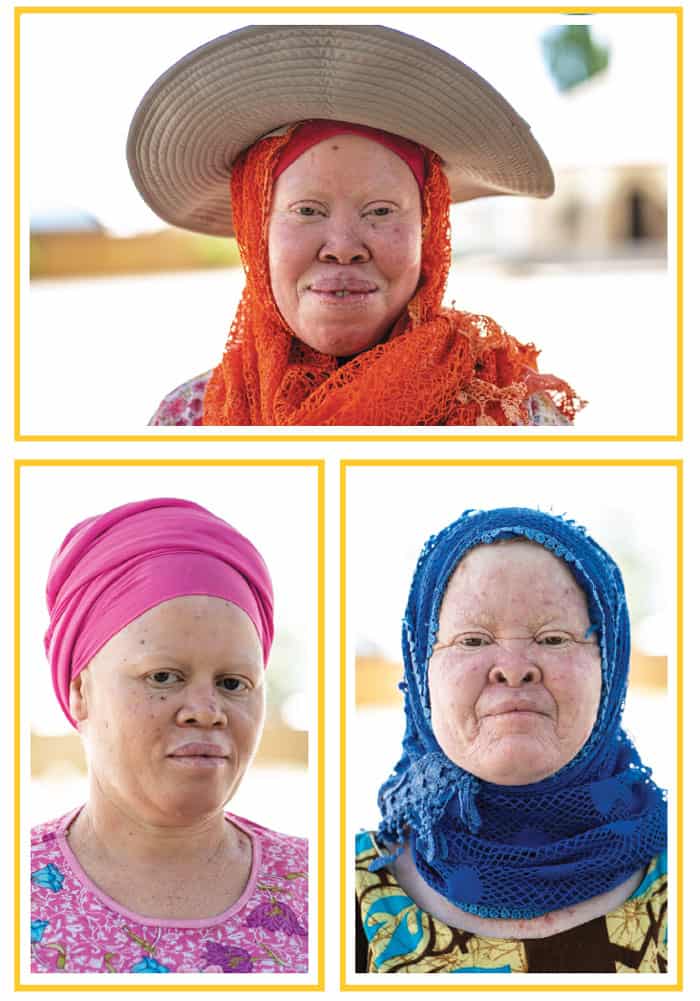

Fadhili Eliakunda Mbonea (left) serves as the Temeke District secretary of the Tanzanian Albinism Society. Salama Kassim (center) and Samuel Herman Muluge are members of the program founded by Maryknoll Father John Waldrep in Dar es Salaam for people living with albinism. Tanzania has one of the highest rates of albinism in the world. (Gregg Brekke/Tanzania)

Since that first seminar, the parish has hosted three well-attended events with a program of speakers and a meal. He says the parish would have hosted more were it not for COVID-19 restrictions.

Held in conjunction with a district-wide association for people with albinism, the parish-hosted meetings are places of connection for people with albinism. Some couples have even met as a result of the gatherings. With financial assistance from the parish and other groups, the association distributes sunscreen, helps purchase sun-protective clothing and assists with covered transportation.

Fadhili Eliakunda Mbonea — who himself has albinism — serves as the Temeke District secretary of the Tanzanian Albinism Society, which also provides referrals for health care, counseling, microloans and various other social services.

“We want to provide a place of acceptance and understanding,” says Mbonea. “These gatherings, the meals and conversations with church members, have helped to overcome so much misunderstanding.” He continues, “Stigma and old ideas about why people have albinism are the single largest obstacle to our ability to flourish as individuals, as people.”

The group works towards capacity building, to assist members with access to financial resources, health care and mental health services. “The economic impact of having albinism can be quite high and even today some employers don’t want to hire us,” Mbonea says. “Though we are business owners, doctors, lawyers, teachers and other professionals, many in our group have financial struggles.”

Albinism is a rare condition, both on the African continent and elsewhere. But in Tanzania, an estimated one in 1,400 people are affected. Scientists believe that close tribal alliances in East Africa result in a high rate of genetic transmission.

Amplifying its perceived mysterious nature, the genetic trait can skip one or more generations before manifesting again; non-albino parents can have offspring with albinism and vice versa.

One participant at the gathering, Salama Kassim, shared that none of her three children have albinism. Salama also said that she felt very accepted growing up in a nearby village, where the only difficulty she experienced was poor eyesight.

(Clockwise, from top) Zainabu Mangara, Amina Lameck and Adelina Muluge join a program for people living with albinism at St. Theresa of the Child Jesus Church in Dar es Salaam. (Gregg Brekke/Tanzania)

“I didn’t feel a lot of discrimination as a child,” she said. “In fact, the teachers and students looked out for me. If we were outside and it was very sunny, they would move our activities inside so I could be protected.”

But being an adult living with the condition, Salama says, has not been as easy. She hasn’t been able to find work in recent years, especially since the pandemic began. She was able to help her youngest child attend school only until second grade.

“There are many challenges,” says Salama. “If I open a roadside stand, people won’t buy from me when they see me.”

Another participant, Siwema Abdalla, says she began to experience discrimination when she entered secondary school at the age of 13. At first, Siwema was put into a special education classroom by a caring teacher who had taken a personal interest in assisting students with albinism.

“This teacher died of cancer and things got much worse,” Siwema says. “We were subjected to electroshock and other abuses.” Things improved, she says, when she was moved to a regular classroom. To support her family, Siwema now runs a small business lending items like dresses and formal wear.

“While I think we’ve made a pretty profound impact, there is still a lot more to do in the ministry with people with albinism,” says Father Waldrep. The priest, who in 2021 relocated to Nairobi, Kenya, to oversee vocations, returns regularly to Tanzania to continue the ministry.

The missioner says he feels compelled to respond: “It’s education and healthcare and just basic needs,” he says. “They can’t pay their rent and they need food.”

Providing for their material needs is not the only way Father Waldrep accompanies people living with albinism. He offers attentive pastoral care and a compassionate presence.

“Most of all, these are God’s children,” he says, “They just need someone to sit with them.”

Featured image: Maryknoll Father John Waldrep (grey hair) and Seminarian Kabaka Leonard (on right, in back) meet with people living with albinism at St. Theresa of the Child Jesus Church in the Buza neighborhood of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, as part of Father Waldrep’s ministry. (Gregg Brekke/Tanzania)

![]()