A returned Maryknoll lay missioner draws upon his experience and ability in working with refugees from Afghanistan.

For returned Maryknoll Lay Missioner Merwyn De Mello, the impact of the cascade of violent events over the last year including the withdrawal of the United States military forces from Afghanistan, and its chaotic aftermath, has been painful to watch. Yet, the influx of tens of thousands of refugees fleeing that country has also meant reconnecting with a people he considers among the most hospitable in his experience from living in different parts of the world.

Last summer, the world witnessed the chaos of throngs of Afghans swarming the airport in Kabul, desperate to escape the country’s takeover by the Taliban. Having worked with his wife, Kirstin, in a peacebuilding project in Afghanistan from 2014 to 2017, De Mello felt “a great deal of sadness, anxiety, and concern” for people he knows there.

“The situation of my former colleagues, is precarious,” he says, remembering the Afghans he worked with. He also worries about his many friends, the Afghan people in general and what life will be like for those who were unable to leave.

“Of course, my fear, from my colleagues and friends to the common people like those selling vegetables on carts, is how are they going to live through this?” he asks. The plight of the people he had known and befriended while living in Kabul haunts him.

De Mello, who speaks Dari, which along with Pashto is one of the two official languages in Afghanistan, takes some solace in his knowledge coming from his personal experience of the Afghan people and the culture. “There is a great amount of resilience in the people of Afghanistan,” he says. “So they find a way. They have survived decades of war and conflict and continue to find a way to exist and to live.” “But” he adds, “this could be one of the most challenging times thus far in their turbulent history.”

Merwyn and Kirstin De Mello receive a Shona language class from a language teacher in a Jesuit parish community just outside Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe. (Courtesy of Merwyn De Mello/Zimbabwe)

At the time of the US withdrawal, De Mello was volunteering in El Paso, Texas, at a shelter run by the Annunciation House hospitality network for migrants. He began receiving several requests from people who knew of his experience in Afghanistan to help with the incoming wave of Afghans. He had the opportunity to assist a number of Afghan families that passed through the House where he was volunteering. When his commitment in El Paso ended, De Mello returned to Washington, D.C., where he lives, and offered his services to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB).

Since December, he has been volunteering, through the USCCB, at the Operation Allies Welcome project in Montgomery County, Maryland. The site has housed a large number of Afghans, including families receiving medical treatment.

“The need in some cases was pretty dire,” he says. “These were individuals with urgent need.” Some have pre-existing illnesses or conditions; others were injured just prior to the evacuation. Many could be carrying the scars of trauma from their experience. To get to this site they and family members had transited through one or more countries and spent time in one or more military bases. Now they are at sheltered at this site to be treated at appropriate medical facilities in the area.

“The USCCB’s Committee on Migration and Refugee Services is responsible for coordinating on-site services,” De Mello says. The goal, he explains, was to help prepare the Afghans for resettlement in the United States. Services included cultural orientation, English as second language classes, orientation to the legal process, and activities dedicated to the particular wellness needs of the women, men and children populations.

“I expressed my interest and was quickly integrated into the program because of my Dari language capacity and my familiarity with the Afghan culture. An underlying value for me is my love and concern for the Afghan people,” he says.

In Japan, Merwyn De Mello visits homeless friends who lived in cardboard boxes on a paved walkway along Tokyo’s Sumida River. Every week De Mello delivered them rice balls made by a group he belonged to, composed mainly of elderly Japanese women and a Franciscan priest. (Courtesy of Merwyn De Mello/Japan)

De Mello says his extensive cross-cultural experience was also a major asset in this service. Born in Kenya of Indian descent, his family moved back to India when he was 13 years old. He is an Indian citizen with permanent residency in the United States. In 1994 he began serving with the Maryknoll lay missioner, first in Japan and then in Tanzania. In Japan he was part of a platform of Japanese lawyers and Burmese activists that supported primarily Burmese asylum seekers in their quest for asylum and in Tanzania he worked in refugee camps for Burundians fleeing the violence in their country.

He returned to the States in 2003 to pursue a masters degree in conflict transformation and peacebuilding at the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding (CJP) at Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia. He and his wife met during their studies at CJP. They married in 2006 and served together with Maryknoll Lay Missioners (MKLM) in Zimbabwe until 2008. After a year’s sojourn in Mumbai, India, they returned to the U.S. where Merwyn worked in Ossining for MKLM doing recruitment and orientation. The couple then moved to Chicago, where they served together with Community Peacemakers Teams (formerly Christian Peacemaker Teams) and participated in community-based restorative justice processes. After a couple of years, they decided to follow their desire to serve overseas again.

“We felt that our passion for overseas service was not over yet,” De Mello says. “When Afghanistan came up as a possibility, we were drawn towards it.” De Mello had lived in countries where Muslims are in a minority, in Kenya, India, Tanzania, and he and Kirstin were drawn to the possibility of serving in a peacebuilding capacity in a Muslim-majority country. Previously, De Mello had worked for Kuwait Airways in the Persian Gulf where he traveled widely. Interactions with colleagues from the Arabic-speaking world opened his eyes to the complex and long-standing conflicts in the Middle East.

The couple arrived in Kabul in 2014 as volunteers with the Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) assigned as peace advisors to a project of an MCC partner. They worked there until 2017, transitioning then to Bangladesh where they served until 2020, also as peace advisors to MCC projects.

“While I lived in Afghanistan, I interacted with all kinds of people in a variety of settings, as much as I could given the stringent security measures,” he says. His Indian nationality, willingness to wear the Afghan male attire — the perahan shirt and tunban pants — and his growing dexterity with speaking Dari were bridge-builders with the local people. Even amidst the numerous security challenges, local shopping and marketing were, for him, social events and avenues to building circles of friendship. The couple made a point of getting to know their Afghan neighbors. Once again the Afghan spirit of hospitality or mehman nawazi facilitated the ease of their visits with their neighbors, not only on special religious and national celebrations, but also for cups of tea on weekends.

Furthermore, De Mello notes, the centuries-long cultural ties between India and Afghanistan, and India’s commitment to economic and developmental investment in the country, played in his favor.

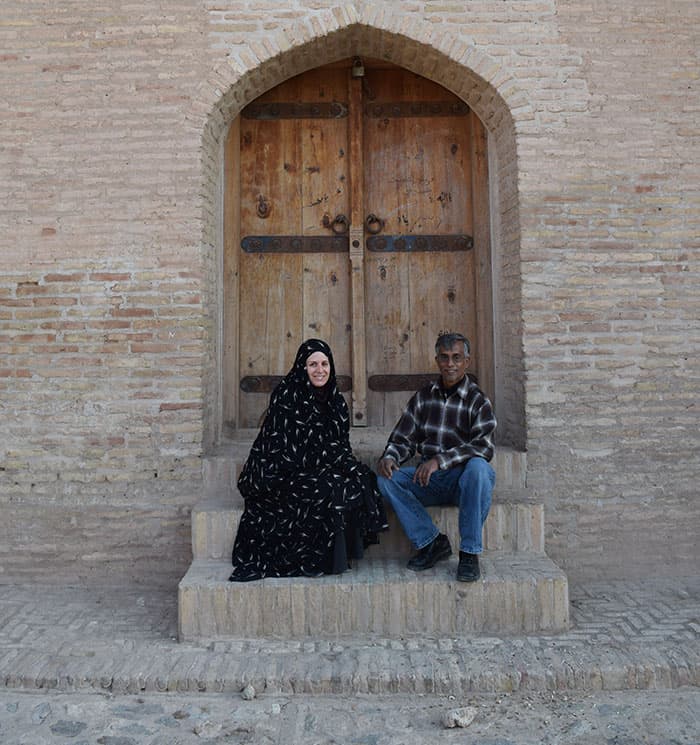

Kirstin and Merwyn De Mello seated at the doorway to an ancient masjid, or mosque, in Herat, the third-largest city in Afghanistan and an historic site once part of the Silk Road between the Middle East and Central Asia. (Courtesy of Merwyn De Mello/Afghanistan)

De Mello says relationships with his neighbors and the local vendors also protected the couple, because people watched out for them. “Sometimes I would be walking on the streets and a shop-owner or a vendor on a cart would pull me aside and say, ‘Please come and have tea with me … it’s better to sit in my house and have a cup of tea because we see some strangers roaming around. It is not safe on the street for you. Okay?’ ”

That was part of the Afghan code of honor: to protect the guest, the foreigner, he says. “The hospitality and protection offered to a guest transcends differences of race, religion and economic status,” De Mello says. “Your being a guest in an Afghan home is a blessing from Allah to the family; protecting the guest is like an oath of honor.”

As De Mello worked with the new arrivals from Afghanistan at the Montgomery County project, he again experienced the Afghan hospitality he had known in Kabul.

While his work in Maryland involved providing cultural orientation, supporting English learning and helping with legal orientation, De Mello feels he also served as a bridge between the Afghans and the many other support staff serving them.

“Because of my cultural sensitivity and ability to converse in Dari I would get requests, from both the Afghans and the support staff, by people who sought to clarify things between each other or needed more information,” he says.

Merwyn De Mello facilitates a teaching-learning session in Kabul, Afghanistan. De Mello worked in Afghanistan in a peacebuilding project with his wife, Kirstin. (Courtesy of Merwyn De Mello/Afghanistan)

“Many Afghans had a natural connection with me because I worked and lived in Afghanistan, and, secondly, due to the close relationship culturally between Indians and Afghans,” he says. “So, that special relationship, that bond, which I had during my three years in Afghanistan, transferred to this environment.”

An integral part of the USCCB’s Operation Allies Welcome project team are a group of interpreters originally from Afghanistan. Working alongside them rekindled memories of De Mello’s time and relationships in Afghanistan. This group embraced him into their midst as a brother, happy to converse in Dari. They invited him to share meals with them. “They invited me into their midst, and I sat with them and I ate the delicious home-cooked Afghan food. Once again I enjoyed that special Afghan hospitality, this time in this country, both from the refugees with whom I had a heart connection, and this warm, wonderful group of interpreters.”

Reflecting on how harrowing the last months have been for the Afghan community at the project, from enduring the fear, pain and chaos of the clamor to get out of Kabul to their initial stays at military bases in the U.S. and to the hotel in an urban U.S. environment, they are still faced with an uncertain future: the challenges of resettlement, De Mello says.

“I think this is a daunting phase coming up for them now, when they will be actually in their resettlement environment, in their homes, and they have to negotiate the system for housing, employment, money management, education, health, transportation, immigration,” he says. So, as the Afghans move on to their new homes and USCCB winds up its work at the site, De Mello vows, “I will continue to accompany at least those I got to know well, with whom I have forged a relationship.”

“My wife, Kirstin, and I were new to Afghanistan,” he says. “We were the strangers – you know that biblical scripture, ‘strangers in a foreign land.’ In all of the places where we have lived in, we have received a warm and generous welcome, but we have never experienced elsewhere the kind of hospitality we experienced in Afghanistan.”

Featured image: Merwyn and Kirstin De Mello are pictured in Nepal on retreat with the Himalayan Mountains in the background. The couple served with the Mennonite Central Committee in Afghanistan from 2014 to 2017, and then in Bangladesh until 2020. (Courtesy of Merwyn De Mello/Afghanistan)