Maryknoll Father Michael Bassano describes life for internally displaced persons in a U.N. camp in Africa.

People ask me, “What is it like to be an internally displaced person?”

I answer from my experience as the chaplain in a U.N. camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in South Sudan. Our camp, about six kilometers (3.7 miles) outside the northeast town of Malakal, is one of the most congested camps in the country. Approximately 30,000 people are cramped next to each other in plastic tarps or tin-sheet houses. Each family receives a two-month supply of sorghum, cooking oil, soap and cereal mix for the children, which is provided by the World Food Programme and is just enough for them to live on.

These people have been here since they were forced to flee their homes during the country’s civil war that began in 2013, when President Salva Kiir, of the Dinka ethnic group, accused Vice President Riek Machar, of the Nuer ethnic group, of attempting a coup d’état.

At a U.N. project on COVID-19 awareness, a youth shows her drawing of the need for handwashing to prevent the spread of the virus. (Courtesy of Michael Bassano/South Sudan)

The conflict ignited old feuds between the country’s multiple ethnic groups. It escalated into a war that claimed some 400,000 lives and displaced millions of others, within and beyond South Sudan’s borders.

When I first arrived in this camp in November 2014, we had no place to worship and had to ask the United Nations for help. We were given the use of a small tent for Sunday worship. We then moved to a structure of plastic sheeting and wooden poles and eventually to a bigger church made of zinc tin sheeting.

Our Catholic community was composed of three ethnic groups: Dinka and Nuer as well as the Shilluk. Our goal as the people of God with all three groups represented was to show to all in the camp that we could live peacefully together as one family of God.

Achieving that goal has been a struggle. People still remember the fateful days in February 2016 when government soldiers broke through the fence in our camp and armed the Dinka people living here. Together the military and the Dinka began shooting at the Shilluk and Nuer people. They burned all of the Nuer homes and one-third of Shilluk homes. The Dinka were then escorted to Malakal to occupy the homes of the Shilluk. Such painful memories will take a long time to heal.

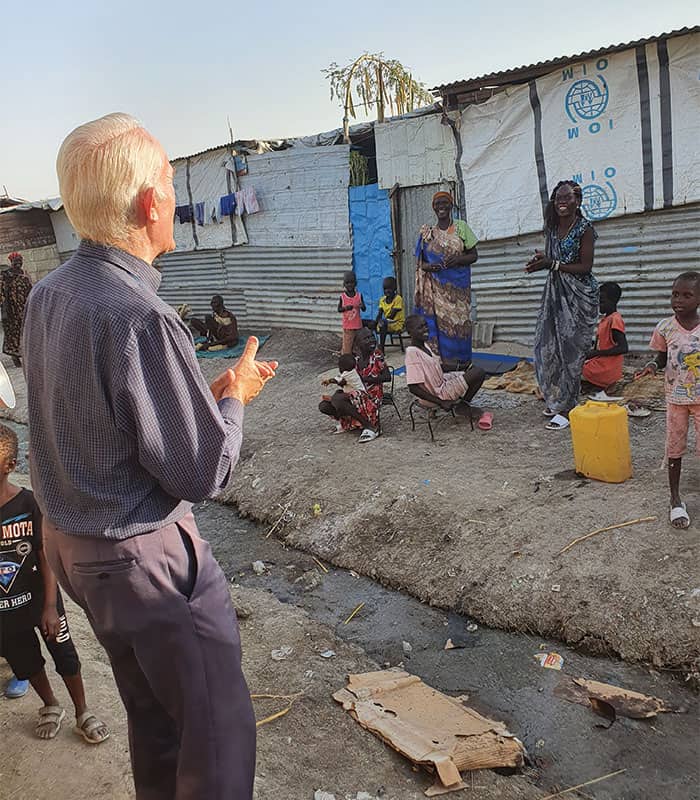

Outside their houses, mothers and children in U.N. camp for displaced persons greet their chaplain, Maryknoll Father Michael Bassano. (Courtesy of Michael Bassano/South Sudan)

With God’s help, we in the camp have become a vibrant community of faith. My primary role has been not only presiding at the Eucharist on Sundays but animating and encouraging all the activities of a typical parish, such as: Legion of Mary, youth group, adult and children’s choirs, religious education classes for those preparing for the sacraments, and Bible study.

Many U.N. organizations and community leaders in the camp have asked to use our church for workshops on human rights and peacebuilding. Our church has come to be recognized as a place of welcome for all.

When COVID-19 closed all houses of worship in March, we decided at the suggestion of our Bishop Stephen Nyodho to record and broadcast our liturgical service over our public radio station, Nile Radio. We became a church of the radio waves!

Living in an IDP camp for so long has certainly taken its toll on the people. They want to return to their homes. The United Nations is encouraging them to do so, but they are afraid to leave because of sporadic fighting throughout the country that persists although a peace agreement was signed in September 2018. Around our area of Upper Nile State, one of 10 states in South Sudan, there is political instability because we have no appointed governor. Interethnic fighting continues, resulting in the rape of women, abduction of children and cattle raiding.

Just before COVID-19 prevented him from visiting the U.N. camp, Father Bassano maintained social distancing while greeting the children there. (Courtesy of Michael Bassano/South Sudan)

A young woman of our church named Rebecca Lochano lost her uncle recently. He was the attorney general of Malakal. A member of the Shilluk ethnic group, he was killed by a gunman of the Dinka group. Rebecca, who is Shilluk, cannot understand why such killing continues against her ethnic group, now the camp’s largest group.

“This is why we cannot leave the camp,” she told me. “No matter where we go, our homes are occupied by another group and we fear for our own safety, that if we leave the camp, we will also be killed like my uncle.”

Chanchuok John, the leader of our youth group, is tired of living in this camp and longs to go home and continue his career as a teacher. “But how can we leave this place when there is still no peace in the country and we fear for our lives if we leave here?” he asks. “I am of the Shilluk tribe and all our lands here in Upper Nile have been taken over by another ethnic group. Our land has been grabbed and taken away from us.”

The journey to peace, reconciliation and justice is still a long road ahead. So, our internally displaced people remain in the camp with the hope of one day returning home.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 is spreading in the camp. As of the middle of October, we had 46 confirmed cases in the camp, out of the total of 112 in Upper Nile State. With people living so close together here, the head of the U.N. camp said she is “concerned the camp will become the epicenter of the virus in Upper Nile State.”

Overall there were almost 2,800 cases throughout the country.

I am restricted from going into the camp because of COVID-19 safety concerns for people my age (71), but there are still things to do. I go around every day encouraging our U.N. staff and keep in touch with members of our church through phone calls.

Recently, one of the youths of our church, Hadia Duoth, called me and said: “Father, how is the coronavirus with you?”

I told her thankfully it was staying away from me! I asked her if she and her family were OK and keeping the health guidelines. “We are fine and not sick,” she said.

We finished our conversation hoping that one day we will see each other again, celebrating in our church with our faith community.

Featured Image: Before COVID-19, Father Bassano visits U.N. camp outside Malakal. (Courtesy of Michael Bassano/South Sudan)