Lessons learned from the AIDS pandemic help Maryknoll priest in Kenya minister in today’s COVID-19 crisis

The coronavirus pandemic is a déjà vu experience for one Maryknoll priest working in healthcare, a nightmare revisited from the last global epidemic: AIDS.

When the first warnings that a new, mysterious and deadly virus had appeared in China early this year, Maryknoll Father Richard Bauer had flashbacks to the 1980s when as a seminarian he volunteered as a pastoral worker at San Francisco General Hospital in California.

Then the virus known today as HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS, was sweeping through two particular populations: intravenous drug users and homosexual men. Then, as now, the mysterious virus claimed not only the sick but the healthcare providers unfamiliar with the pathogen they had never encountered before.

“I actually started all of this on the infectious disease floors of San Francisco General in 1982,” Father Bauer says. “I always say that so many of my friends and colleagues from those years died from the virus, but so many more burned out from the intense work.”

Early this year, Father Bauer, who now works in ministry with people with HIV in Nairobi, Kenya, was alarmed at what he was hearing about COVID-19, first from China and then from Iran, Italy and Spain, and moved to prepare for the unfolding health crisis that he feared would soon reach East Africa in its spread around the world.

Maryknoll Father Richard Bauer talks to community healthcare workers at Catholic AIDS clinic in Mathare, Nairobi, Kenya. (Sean Sprague/Kenya)

“I think there were some who called me histrionic and overreacting,” the missioner from Santa Barbara, Calif., says, “but I made sure in February and March that we started purchasing that personal protective gear and training our staff and community health workers for their own safety.”Father Bauer knew the pandemic was not only going to claim the lives of countless victims, but was going to exhaust the medical professionals needed to care for the sick and dying.

“Right now, Kenya has over 25,000 cases and about 413 deaths—not as bad as the public health disaster unfolding in the United States, but bad,” says Father Bauer. “The private hospitals and ICUs are now full, and reportedly, the public hospitals are sometimes turning COVID patients away.”

Because only 2 percent of the Kenyan population is over 60, the country has not yet seen a huge amount of deaths, he says. “But still, without the ICU and ventilator support, we are having to do much more hospice and palliative care. Positive COVID-19 people without symptoms are asked to self-quarantine at home.”

Father Bauer, who has degrees in divinity and social work, is a board-certified chaplain, and the focus of his work as a priest and as an experienced healthcare professional has been to integrate comprehensive care, the physical, emotional, social and spiritual into clinical healthcare. This includes palliative care that addresses the suffering of individuals facing a life-limiting illness.

Tony Otieno, EDARP Clinical Officer, providing a clinical exam with a patient during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nairobi. (Photo courtesy of Richard Bauer/Kenya)

In a pandemic crisis such as HIV and now COVID-19, Father Bauer knows that care must extend to the medical personnel, be it doctors and nurses or home and community healthcare workers, such as those working in the HIV care and support program in which he ministers in Nairobi called EDARP—the Eastern Deanery AIDS Relief Program.

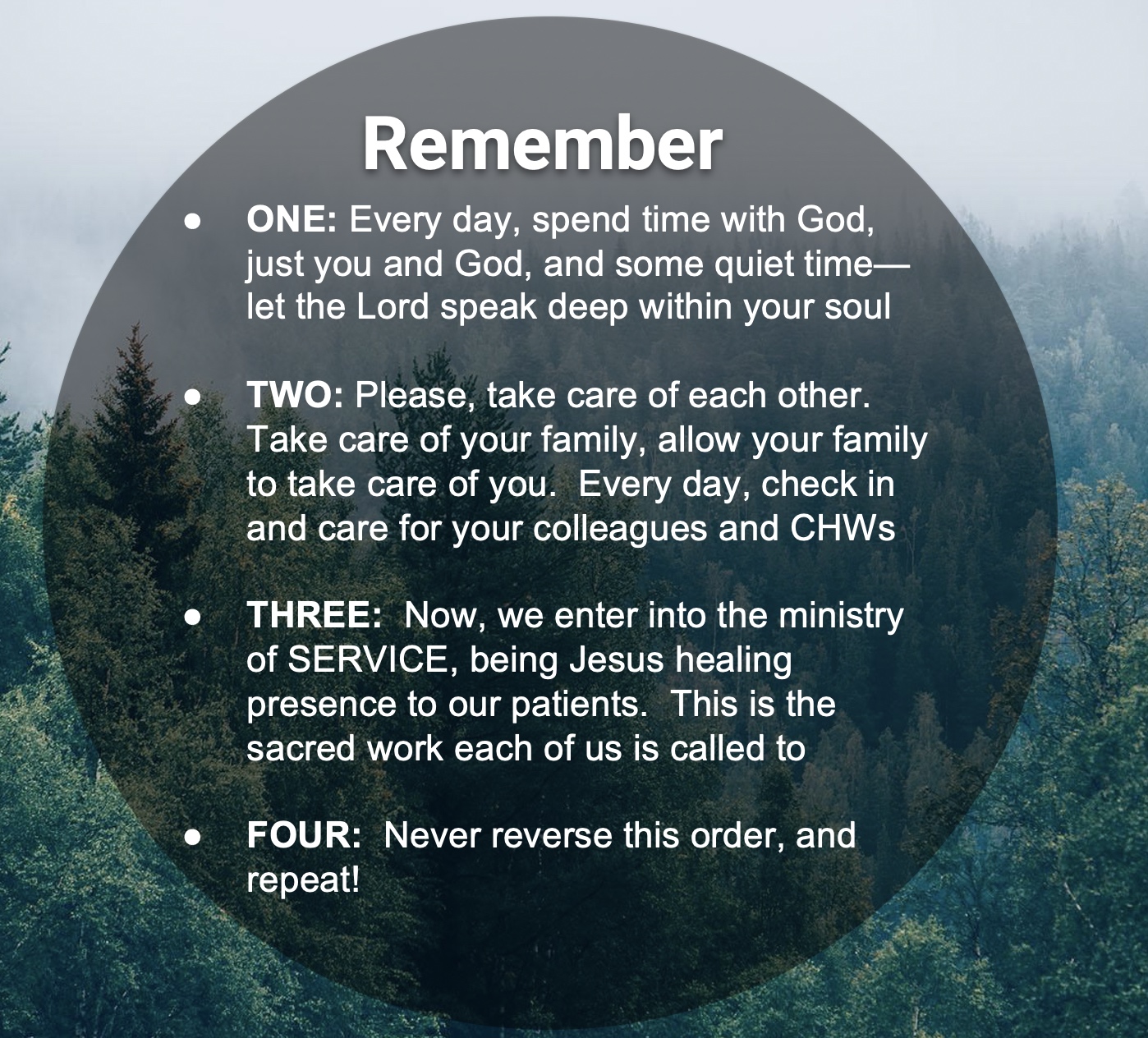

Not only did Father Bauer push for EDARP to stock up quickly on personal protective equipment for the staff and health outreach workers, he emphasized a four-point protocol he helped develop during the AIDS pandemic before the development of antiretroviral drugs made AIDS a manageable disease instead of an automatic death sentence.

The protocols—or rules as he calls them—-are intended to help healthcare workers cope with the crisis by protecting themselves and so remain healthy physically, emotionally and spiritually so they can keep on caring for others.

“Number one, spend time every day with God, however you understand that word or that concept,” Father Bauer says. “We cannot give to others unless we’re nourishing ourselves. And that can be prayer or Bible readings or a walk in nature or music, but you have to feed your soul if you’re going to do this work.”

Maryknoll Father Richard Bauer participates in a webinar on responding to pandemics. (Screenshot courtesy of Richard Bauer)

“Number two is take care of each other,” he says. “I really reinforced this with the staff. So it’s really taking care of each other and reinforcing that this is an incredibly stressful time.”

Number three, he says, is “take care of the patients,” and number four is “never reverse this order, and repeat.”

Father Bauer says those four basic rules have been the keys to success for him in working to manage and support staff in any clinical program.

He says he has one more rule but sometimes gets his “hand slapped” for including it. “But I’ll tell you,” he says, “and then five, take care of the donors, and never reverse that order.”

For Father Bauer, the fifth point is important because it is essential that everyone does what they can in a crisis. For some it is direct patient care and for others it is making that care possible. In all cases, it is saving lives and making the human connection with each patient. The order of the rules matters simply because a healthcare worker who is sick or burned out can no longer take care of others.

“This is a time globally of acute anxiety,” he says. “Grief, trauma and moral distress are going to be happening now and in the future. This is not only grief about loss of life, but grief about the loss of social contact, grief about losing your job, grief about changes in family and community. The mental health consequences of physical distancing can be overwhelming. I’m doing some remote support and care for colleagues at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. I think the grief and the post traumatic stress is going to be a huge issue.”

Maryknoll Father Richard Bauer’s four point protocol for healthcare workers to follow during a pandemic. (Screenshot courtesy of Richard Bauer)

That makes the need to remember spiritual support, as well as emotional and physical support, so important in this unprecedented time, he says.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Father Bauer finds himself reflecting on the similarities between this time of pandemic and the AIDS crisis in San Francisco in 1982. A huge part of that, he says, is fear. “There was so much fear going on, and I see the same thing with COVID-19,” he says.

In response to this anxiety, he asks himself and others the question of how someone goes from fear to faith, and he draws on the Gospel account of the disciples of Jesus at Pentecost.

“They were afraid the next person to be executed and crucified would be themselves,” he says. “They hid away in this upper room, and in that upper room, I think a couple of things happened. They stayed together as a community, and number one, they spent time with God; they prayed.”

One of the gifts the Apostles received in the upper room was that of listening, which is part of the gifts of understanding and wisdom, he says.

“As we move from the fear of COVID, the fear of HIV, one of the gifts of the Spirit is this gift of deep listening,” he says. “The Apostles listened to Jesus. The crowds stopped to listen to the Apostles, and this is what changed human history forever.”

Even in this time of restrictions, physical distancing and stringent protocols for infection control, it is still important to take care of oneself and others, and stay present by listening, Father Bauer says.

“And that’s listening to the cries of the poor, listening to the pain and the fears of the sick and the dying, listening to people who are lonely and afraid,” he says. “But first of all, listen to God.”

![]()